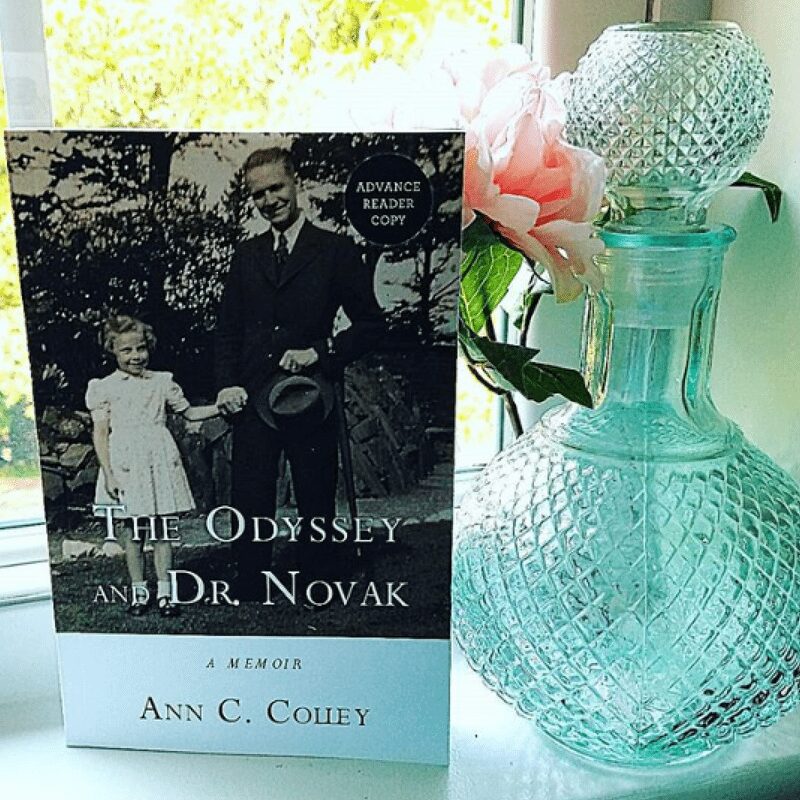

In Ann C. Colley’s intriguing memoir, the author recalls a time from her childhood when she met the mysterious Dr. Novak, a Czechoslovakian. Her life experiences after this encounter will forever be with Colley and in this exclusive excerpt, she gives readers a sneak peek of this compelling story.

The December 1995 journey to Lviv is a trip into the unknown and, as such, still rattles down the tracks of my memory. With our passports close to our bodies and our money distributed in various pockets (we have to take American dollars), we arrive at the Warsaw-Gdansk Railroad Station at eight in the morning. The snow is blowing; the train station, lit by hollow, harsh fluorescent bulbs, is virtually empty, except for a few people milling around under rafters covered with puffed-up pigeons huddled and sheltering from the cold. Heeding the warnings of

Agata, we speak softly, sotto voce. We are to leave from Platform 3, so, after crossing the tracks on foot, we join others either lugging massive plastic bags of goods or waiting silently.

The train looms out of the early darkness. Bulky, blackgreen, and full of smoke, it emerges from a Soviet past. We find our wagon and step into a dark, cold, and grimy world that will be ours not only on the train for the coming fourteen hours but also for the next fortnight in Lviv. A ghastly dimness makes it hard to grope our way through the train, feel our way past minute buckets of coal, and enter our second-class compartment. Mud, melted snow, and months of memory streak the windows. Ratty stained curtains, stamped in one corner with an official seal, slouch in a corner of the window frame. Bunks with blankets, knotted and inhabited by the germs of humanity’s history, occupy both sides of the couchette. The pillows leak feathers; the covers are gray, rough, and used. A small table extends from under the window.

We are relieved to have the compartment to ourselves, for the travel agent has told us that women and men are segregated on the train and that we, therefore, shall not be able to be together, unless we pay off the conductor. It is ours for an hour, until a university student, who is going home for the semester break, unexpectedly joins us. (Young people from Lviv quite often attend Polish universities.) Communicating with bits and pieces of Polish and Russian, we learn that she was ill after the Chernobyl accident. “I’m fine now,” she claims. Once the polite exchange is over, our companion nimbly climbs up to the top bunk and disappears, dead to the world, under the bedding we have rejected.

When the train laboriously moves away from the station, we cannot conceive why it will take fourteen hours to go approximately180 miles to reach our destination. Before too long, however, we begin to comprehend why the journey is to be long and dreadful. The compartment grows colder and colder. Soon we learn that there is no food or drink, so for the next fourteen hours we live off two small boxes of juice and three chocolate wafers we find buried in our pockets. The occupants in the adjoining compartment know better and have brought tins of sausages and bottles of sauerkraut. The putrid smell of our neighbors’ repast coasts through the vents and mingles with the smoke from a coal fire the lady conductor stokes and on which she warms water for her tea. The toilets are too awful to use. A dirty rag lies over the seat, which is never cleaned. We both refrain.

From time to time the train pulls into stations and stops, but no one, it seems, gets either off or on. When we arrive in Lublin (the largest Polish city east of the Vistula River), there is perhaps a change of engines, and then the train seems to go back the way we came. It is now impossible to see anything out of the window. Though it is growing darker and darker both inside and out, there are no plans to turn on any lights. My feet are like stone.

After enduring seven hours of sitting in complete darkness, we come to an abrupt stop. Irving, with the help of a flashlight, has been snatching furtive glances at paragraphs from his novel while I have been listening to books on tape. When the Polish border guards embark, a few fluorescent lights magically switch on. The officials inspect our passports and then instruct us to leave the cabin so they can search for contraband. The lights go off and we are underway for a while, until yet another set of Polish guards enter and look once more at our passports; they carefully compare photographs to faces. Lights off and move. Soon the train stops again; lights on, and we are asked to fill out declaration forms that are written in Ukrainian (and in small print). What to do? The student in our compartment, like a groundhog from its hole, crawls out from the blankets and helps us while repeatedly exclaiming in Russian, “The trip is a nightmare!”

Lights extinguished; we proceed but not for very long. This time, the Ukrainian guards, wearing their heavy square fur hats, enter and take away our passports and tickets. In the freezing air, their breath trails their commands. After at least half an hour, they return with our documents. The train jerks slowly forward and finally halts at a station full of enormous machinery and lifts. It is like entering some leftover Soviet-style factory or perhaps finding oneself in a frame from a German expressionist film showing massive cogs and wheels laboriously turning, grinding, and producing. As a relic of territorial disputes, the train is forced to stop because the tracks in Ukraine are not the same width as they are in Poland. They are narrow-gauge tracks, so in order for the journey to continue, the train’s wheels must be taken off and narrower ones put on. (This anomaly was recently corrected; new tracks have been built, and high-speed trains now regularly whiz between Warsaw and Lviv.) For several hours, while still seated on the train, we are shaken, jolted, lifted, and pushed. Groans and clanks accompany the train’s moving back and forth. I can stand it no more. I whip out my Sony Walkman and listen to a tape of Helen Reddy singing “I Am Woman”—anything to give me strength to endure the ordeal.

Finally, the train pulls into Lviv. Dazed from the long day that has been night, and not yet fully awoken from the nightmare, we step out into a dim station jam-packed with travelers on their way to I know not where. It is 11:00 p.m. Like lost sheep, we follow passengers down stairs and through unlit, filthy, frozen, dripping tunnels, through puzzling corridors, until we emerge into a domed nineteenth-century grand hall, adorned with clumsy imposing friezes displaying communist hammers and sickles. Brimming with goodwill, our guide, Ihor Markow, greets us and leads us out into the cold night.

Leave A Comment