Caroline Leavitt is the New York Times and USA Today bestselling author of over a dozen novels, and her latest novel, Days of Wonder, publishes April 23rd. We sat down with Caroline to discuss her newest book and all things writing-related.

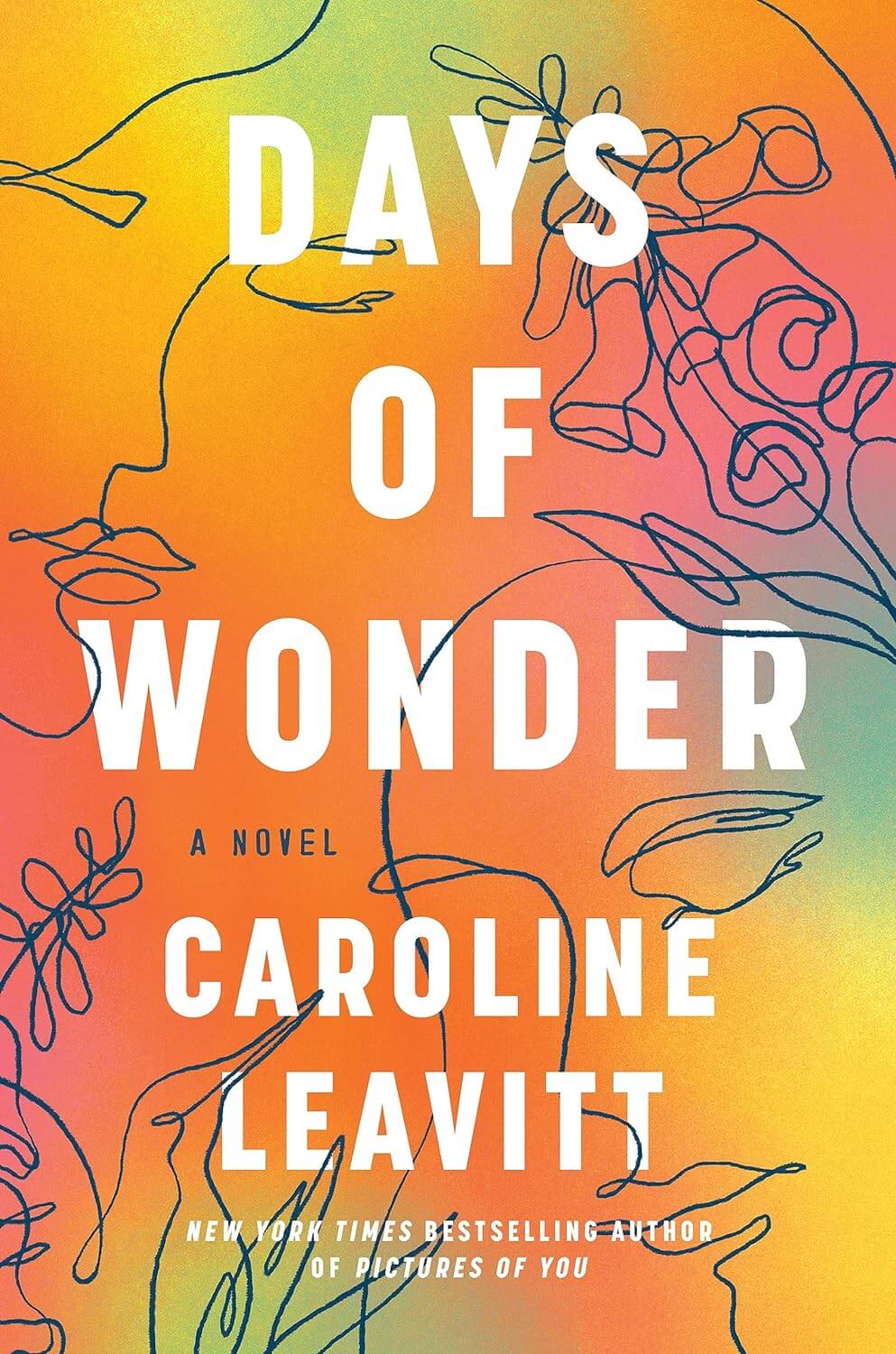

Days of Wonder by Caroline Leavitt

Days of Wonder is about Ellie, a teenager sent to jail for attempted murder, who upon early release from prison, attempts to find the daughter she gave up for adoption while in prison.

Buy the book now: Bookshop.org | Amazon | Barnes & Noble

This interview was conducted by Kailey Costa. Follow her recommendations on Instagram at @KMC_Reads.

Q: There seem to be a lot of novels lately that center around mothers, or motherhood, and especially mothers in very difficult situations. What made you want to tell this particular story & where did the idea come from

A: There are a whole lot of books about mothering and it’s always been something that I was interested in. I had a difficult childhood, not because of my mother, but more because of my father. I never wanted kids until I got older and fell in love and met my husband. Being a mother was a transformative experience for me and I think now women are allowed to talk about the difficulties in being a mother and it doesn’t make you a bad mother if you’re talking about them. My mother died a few years ago, and it got me thinking about my mother and I wanted to bring her alive on the page to keep her with me. That created the character of Helen, which is the same name as my mom.

As far as the idea goes, I was having lunch with a new friend of mine, and one day she said, “I have to tell you something” and she said, “Well, when I was 15 I committed a murder and I went to prison for it.” She said she absolutely did do it, she was really wild then and she really regretted it. She was early released, she changed her name/identity and moved. She was 40 years old when someone found out and they outed her and she lost jobs, friends, it was horrible. When I heard about that, I thought that was something I wanted to write about. I didn’t want to invade her privacy, so I didn’t mention her name and never have and changed every detail. The main thing I was interested in was this whole idea of reinvention. So I changed the book into a Romeo & Juliet story. Two NYC kids from different classes, madly, passionately in love and the boy’s father wants to separate them. It starts as a game, just fantasy and then it comes to the point where they actually will be separated and then it becomes less of a fantasy.

Q: There are a few mother/daughter relationships examined in this story, and this book is as much Helen’s story as it is Ellie’s. Did you always know it was going to turn out that way,with Helen’s story being such a central focus?

A: No, I didn’t always know. I knew there was going to be a mother and as soon as I called her Helen, I started remembering my mom’s life and my mom’s story. When my mother was alive, she didn’t want me to write about her, she was very private. I thought this would bring my mother back to me – the more I wrote, the more I remembered – the stories my mother told me about her growing up, and what a remarkable life she had. It was a delightful surprise.

Q: What did your process look like as you prepared to write about someone who’d been incarcerated and trying to acclimate back into the world?

A: I spoke with Jean Trounstine, she’s a prison activist and writer. She ran a program called “Changing Life Through Literature.” Women who were on probation came to this class. She invited me to this class to meet these women. There were 15 women there, it was incredible. We bonded and they became really honest and open to me. Women’s prison is not like you necessarily see on TV. They made strong friendships and the worst thing was boredom because every day is the same. I found that one prison had an agreement with Bard College. Bard allows prisoners to take Bard classes while in prison and earn degrees. They found that what happened is that it changed the inmates. They knew when they got out of prison, the college would help them get good jobs, not just “felon friendly” jobs. I had endless conversations with Jean and these women and it was really eye opening.

Q: The role of religion plays a big part in Helen’s life and upbringing, can you explain why you chose to make it part of the story?

A: That was my mom’s story, to an extent. She grew up orthodox Jewish. One of 8 kids, daughter of a very religious Rabbi. My mother loved growing up in that community, she didn’t mind the restrictions. After losing her father suddenly, she gave it up, but she yearned for that community the whole of her life. I found three people who had left the Hasidic communities and they all agreed to talk to me. The one question I asked them all was, “What did you miss about growing up there?” and they all said the same thing: that they missed that sense of community, of everyone taking care of you, if you didn’t have money the community would help you, if you were getting married, the community would help you. There was a sense that you would always have someone, you would never be alone. I wanted to give that to Helen, to have her be someone who would’ve stayed forever, and she’s thrust into the world and she spends the rest of her time wondering “What kind of community I can build for myself, how can I recapture that feeling?” I wanted her to be able to do that.

Q: Did you always know how the story would end?

A: No, I didn’t. I do these sort of detailed writer’s outlines so I know I’ve created a story, and then I’ll rewrite it a dozen times. So, no I didn’t really know how it’d end, but I like what I call never-ending stories, which means when you close the book you’re hoping for something and you can imagine it in your mind. I didn’t really know what was going to happen with them, but I have my own hopes for them. There’s possibilities and they have to live to see how it’s actually going to end.

Q: Your novels seem to feature characters in difficult situations with more serious subject matter… what makes you drawn to telling these types of stories?

A: I’m a silly person, silly as in I’m very happy and positive. I’m able to be happy because I write these difficult situations and put these characters in these terrible situations that I always seemed to worry about. I grew up obsessive and worried and anxious, and I find that by giving these situations that I personally worry about, to other characters, I can work through my own anxieties and witness how someone else would get through it and it makes me feel better. It’s like a mental health thing for me to do, rather than have this free floating anxiety about it. Knowledge is power, and now I know exactly what to do. Also, I love drama! As a little girl I had asthma and couldn’t go out a lot, so I watched a lot of melodramas with my mother and I just loved it. I felt exhilarated. I loved being able to participate in that.

Q: Tell us about your writing process. Do you do a lot of outlining before or do you write and see where the story takes you?

A: I think every writer does it differently, for my first eight novels I depended on the muse and would write whatever came out of my head, and I’d end up with 800-page manuscripts, which is way too long. Before I started writing my 9th novel, a student asked if I knew story structure, and I said I wasn’t really interested, but she sent them to me anyways, and I was enthralled. John Truby talked about the story in a way I’d never heard before. I tried it for my 9th novel. First, my novel was only 320 pages as opposed to 800, so that was great, and that particular book became my first New York Times bestseller, so ever since then, that’s what I’ve done. Some people say if you outline it takes away the creativity and I’m here to say, no it doesn’t, it actually enhances it.

Leave A Comment