We are so thrilled to sit down with bestselling, award-winning author Tayari Jones. You may know her from her Oprah’s Book Club pick, An American Marriage, and we’re thrilled for her newest novel, Kin—releasing this month. We got a chance to talk to her about the magical origins of this unexpected historical fiction novel, discuss the questions she is trying to answer in her work and scoop up some of her latest book recs!

She Reads: Tell us about your latest novel, Kin.

Tayari Jones: I think of it as kind of a classic story—friends who’ve known each other since childhood and whose lives take different directions. That’s something we know from Sula, we know it from Peaches [likely referring to The Color Purple], we know it from Best of Friends. There are just so many books like that because I think it’s an evergreen topic. Our friendships are the other love stories in our lives.

So it’s about Vernice and Annie, two friends who’ve known each other since they were infants. What they have in common is that they are motherless. What they don’t have in common is how that happened. Bernice’s mother died in an act of domestic violence before she was a year old, but Annie’s mother abandoned her.

Much of the novel is about this question of hope: is hope a virtue or a detriment? Annie has the idea that one day she could be reunited with her mother, and that hope wakes her up every morning—but disappointment puts her to bed every night. Vernice knows she’ll never see her mother again, so she organizes her life around the hope of marrying and creating for herself the family she never had.

It’s set in the 1950s and ’60s in the South, against the backdrop of the social change leading up to the Civil Rights Movement. And it’s my first time venturing into historical fiction.

She Reads: What was that like for you? How was the research—challenging or exciting?

Tayari Jones: The whole novel was exciting and new, especially because it wasn’t the novel I was contracted to write. I was contracted to do what I usually do—a contemporary novel set in Atlanta. It was going to be about gentrification and whether you can gentrify your own hometown.

I had moved back to Atlanta and was living in a changing neighborhood, and I was wondering, am I gentrifying anything, or am I just coming home? I wanted to write about that—but that wasn’t what wanted to be written.

I’ve never really been that person who says, you don’t choose a story, the story chooses you. I’m not mystical about the writing process. But I couldn’t get that book off the ground. I was writing it, but it felt workmanlike. The prose didn’t have that sparkle—the magic that comes when a story feels blessed.

I do believe there’s something about art you can’t quite put your hands on. Usually my mind puts the ideas forth, and then creativity—the pixie dust—helps. But this time, I wasn’t getting traction. After years of writer’s block, I did something I call word doodling. I use a pencil—sharpened with a pencil sharpener—and just scribble whatever comes to mind, with no expectations.

A story started coming to life. When I realized it was set in the 1950s, I thought, this must be my character’s mother—this has to be backstory. I wasn’t concerned because a rich backstory gives a story solidity. But after about a year, when I was 150 pages in, I realized: this isn’t the backstory. This is the story.

She Reads: I love when that happens—the magic no one can fully explain.

Tayari Jones: The proportion of magic to effort was so different this time that I felt swept up and had to surrender to it. I’ve never been a controlling writer. I don’t outline; I write to find the end. This was the first time I wrote to find the middle.

She Reads: In Kin, how did the early loss of their mothers shape Vernice and Annie as they grow into adulthood?

Tayari Jones: What follows them is that they were each reared by people who didn’t sign up for that. In the ’50s and before—before reliable contraception—babies just happened. Women had babies they could not or would not care for, and aunts and grandmothers often took over without preparation.

Both girls were cared for, but they were never truly mothered. They were never the apple of anyone’s eye. They imagine that their lost mothers would have given them that thing they didn’t have, and they search for it their whole lives.

She Reads: Mothers shape us whether they’re present, absent, idealized, or imperfect. What does Kin reveal about how women inherit both strength and wounds across generations?

Tayari Jones: Everyone is deeply shaped by their understanding of where they came from and whether they were loved. Motherhood represents worthiness. To feel unworthy of love affects every relationship.

Even Annie—she has an address for her mother, but she never goes there until too late, because she’s trying to make herself worthy. She wants to say, I’m not the daughter you should have left. That wound—the feeling of being unlovable—is carried by many of the characters.

She Reads: How do unanswered questions from childhood follow us into adulthood?

Tayari Jones: When you have an unanswered question, it’s not just any answer you want. Everybody has an answer in their mind that they hope to receive. And you could get the answer to a question—and it could actually make things worse. So it’s really not the not knowing. We think it is, because people who want to know always say that: I just didn’t know. But sometimes you may not want to know. That’s what other people—people who do know the answers—keep trying to tell these characters: Are you sure? Because I know X, Y, and Z about my family, and it has not been helpful.

So I think that’s the real tension. It’s our struggle to reconcile our real lives with our imaginations—and how hope, the lure of the imaginary, can actually keep you from appreciating what is already here.

Other people can love you, if you will let them. Someone else can mother you, if you will let them.

Because [Vernice] knows she will never know her mother, she’s able to be loved by Mrs. McKinley. She lets her, because she isn’t holding open a space for her mother—she knows her mother is gone. But Annie, as long as she believes Hattie Lee is still out there, keeps that place reserved. She’s not going to let anyone else take it.

She Reads: Many readers are coming to Kin after An American Marriage. In what ways does this novel continue that exploration, and where does it break new ground?

Tayari Jones: The historical setting is where it breaks new ground. Kin is set in the ’50s; An American Marriage is set in the 2000s. The stories are set fifty years apart, and there are similarities between them. In both, the characters start out in small towns and move to Atlanta as a kind of promised land.

Another thing the books have in common is the way I approach storytelling. There are only so many stories out there—people say seven—but for me, the question is always: what is the question I want to ask?

When I wrote An American Marriage, which is about a couple separated by a wrongful conviction, there’s a familiar expectation that it will be a woman’s brave fight to free her man. Instead, the question I really wanted to ask was: what is reasonable to expect of another person? This is where all that rhetoric about women choosing themselves really meets reality—this is where the rubber hits the road.

I think readers were deeply uncomfortable with a woman who chose herself, because when we talk about choosing yourself, we often erase the consequences of that choice. The act itself becomes the point, and we don’t look at the downstream effects. An American Marriage is very much about showing those downstream consequences, especially in the face of the injustice of wrongful conviction.

In Kin, the question I was interested in interrogating is the idea of searching for one’s mother. The classic story tells us, of course you search for your mother. If someone says, I don’t know where my mother is, we frame it as a brave quest to find her. But I wanted to question that impulse. Is it always better to know? Is it okay not to know? Can we learn to be satisfied with not knowing?

Satisfaction is something I’m very interested in. In real life, people can be satisfied with what they have. But in what my MFA teacher used to call “story life,” if there’s a question, it must be answered—that’s the rule. In real life, you can marry someone who isn’t the person you once dreamed of and still have a good life. In a story, that’s often treated as an unpardonable compromise.

I’m trying to bring into story life the wisdom we already know from real life.

I think some readers prefer a little untidiness in stories, and others find it uncomfortable when something feels too real—when it doesn’t deliver a neat, storybook ending. But I think it’s important that not every piece of fiction be an idealized version of life, or a previously rehearsed one.

I actually think An American Marriage has a happy ending, even though the original couple doesn’t end up together. Everyone in the book is doing okay. They’re moving forward. I believe I resolve my conflicts and my plots—but I try to resolve them the way people do in real life. Real people are reading these stories, and I want a real person to feel seen.

She Reads: I love understanding the questions that started the story: as you were writing Kin, did other questions emerge? Some that arose as the story unfolded?

Tayari Jones: One thing that really struck me—and that I had never fully thought about until I lived inside this novel—was the whole question of reproduction. It’s very difficult for us, as modern people, to wrap our heads around the idea of not being able to control it.

In the ’40s and ’50s, when people had sexual relationships, they were really rolling the dice. Pregnancy was the fear in the back of everyone’s mind all the time. I think we’ve lost that perspective in the present moment, and we sometimes forget how profoundly technological breakthroughs have changed women’s lives. If you cannot control your reproduction, you cannot control anything. And that was something I really wanted to bring into the book.

Another question that emerged for me was how our understanding of what children need has changed. We now believe children need unconditional love—and children’s needs themselves have never changed—but adults’ understanding of how children should be treated has. Children have not changed.

I kept thinking about the extent to which our parents’ and grandparents’ generations were shaped by having their emotional needs unmet, simply because people didn’t yet recognize that children have emotional needs. It wasn’t what we would now call bad parenting. People thought about physical needs—making sure children were fed, clean, clothed, and had access to education if possible. But the idea that children need to be listened to and heard is a very new understanding.

And I don’t think that’s unrelated to safe, reliable contraception.

I think about my grandmother. She had twelve children. Could she really attend to the emotional needs of twelve people? Twelve people—I don’t even teach classes with twelve people. She had more children than I think I could possibly teach.

Now, when people have one child, two children, three children, it’s a completely different experience. The risks were so much higher then—not just because of reproduction, but because of the ability to provide, the lack of access to information, and the absence of guidance about what children actually need. People were doing the best they could with what they came from.

My grandmother once told me that near the end of her life, she only ever wanted two children. She had twelve. She wanted two.

That’s ten extra people. You are their one mother. They are one of twelve—but you are one of one for them.

And that’s the dynamic with Annie. Her mother is one of one for her. But Annie is not one of one for her mother.

She Reads: Is there a moment where your characters surprised you?

Tayari Jones: My main characters don’t tend to surprise me, because I know them. It’s the other people—the secondary characters—who surprise me with what they do. I don’t know them as well, and they’re the ones whose actions affect my main characters.

My mains are solid. I know them. But characters like Hattie Lee, like everyone else around them—each of those people did something where I thought, well, look at you, taking over a page. I have my eye so firmly on the main characters that it’s the side characters who surprise me.

I hadn’t considered how unhappy Bobo was until he told Annie. And I was like, I guess so. I guess so, dude. I see it. I see that.

She Reads: What are you currently reading?

Tayari Jones: I just finished How to Commit a Postcolonial Murder. It’s slim but packs a punch—I cried.

She Reads: What books do you recommend over and over again?

Tayari Jones: Song of Solomon by Toni Morrison because no one is going to question that Morrison is the highest of literary, but, oh, my God, she is a plotting maniac. She is such a plotter. That book is a cliffhanger. It ends with the people on a cliff. And so I like to recommend that to my students, especially, because sometimes I think we feel that the plot is undignified, and I say, bad plotting is undignified. Good plotting is sacred.

She Reads: Any upcoming books you’re excited about?

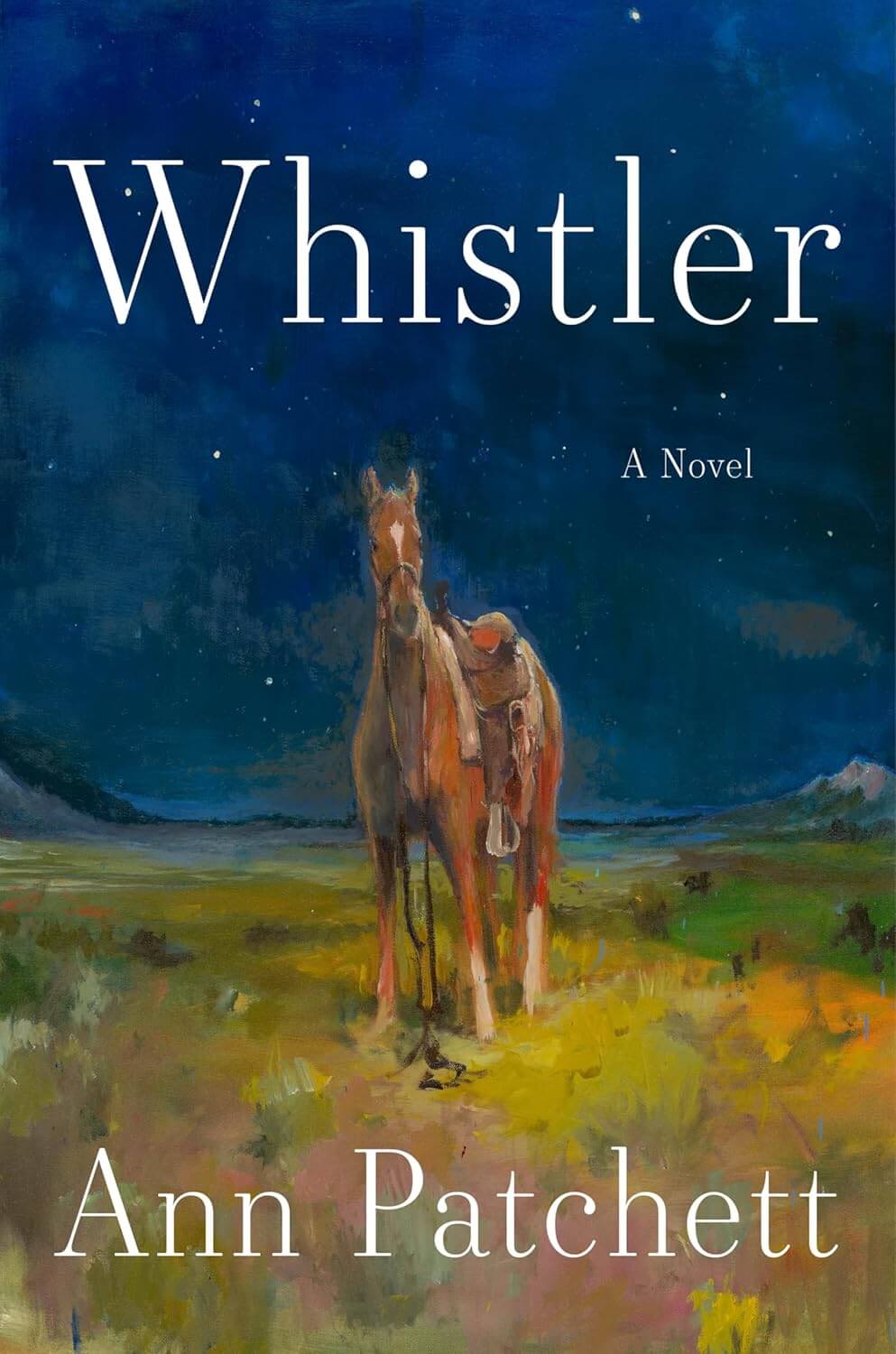

Tayari Jones: Ann Patchett’s Whistler and Nafissa Thompson-Spires’s debut novel The Four Wives and Five Deaths of Richard Milford. Nafissa’s is a slim book that comes out hot—I love that.

And Ann Patchett, I can’t believe she is so good so often. How does she do that?

She Reads: What are you working on next?

Tayari Jones: I think I may finally be able to write the book I wanted to write before. Living in my neighborhood for years has given me new sparks.

She Reads: Thank you so much for your time.

Tayari Jones: Thank you. It’s been a pleasure.

Leave A Comment