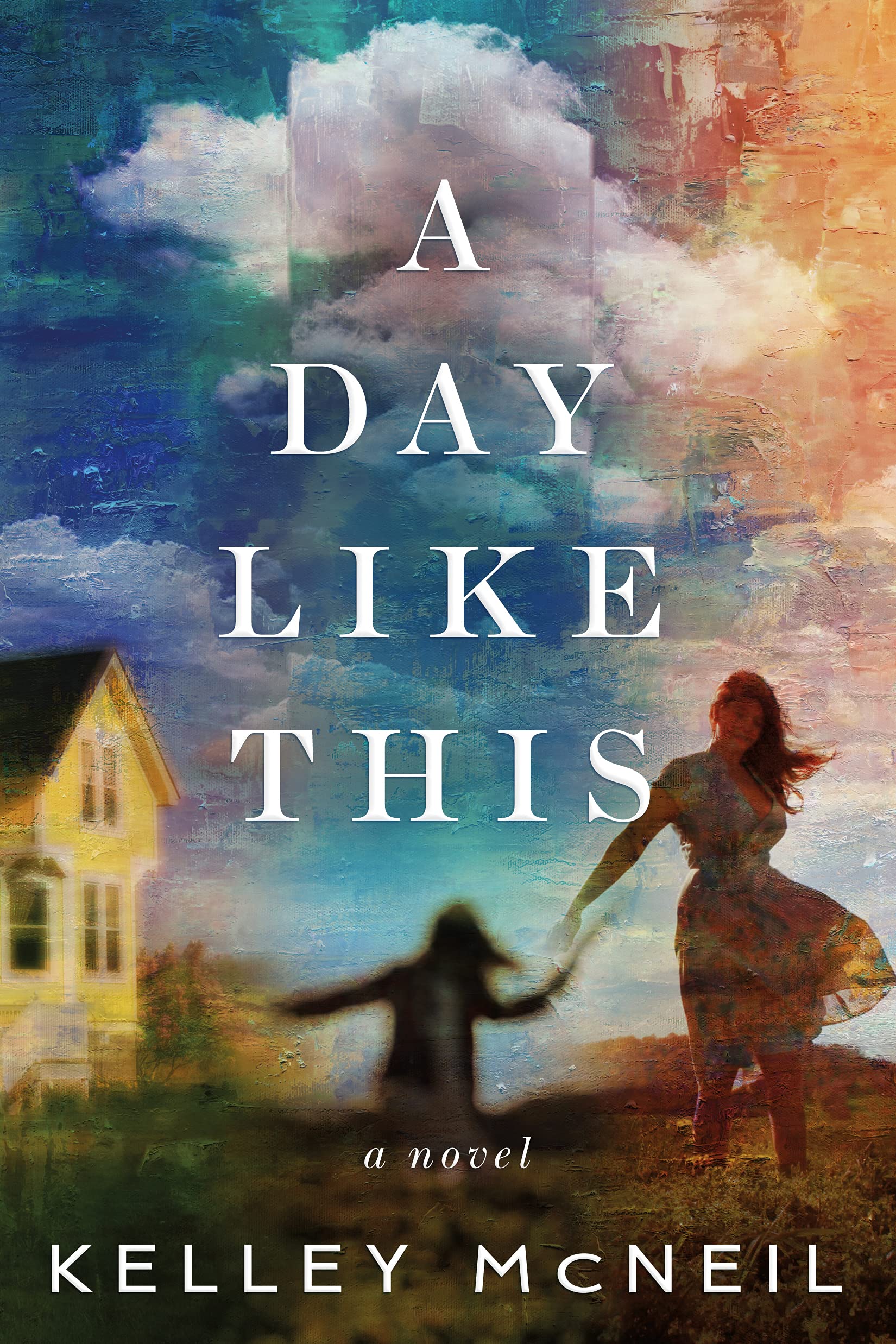

Kelley McNeil’s artful and authentic debut A Day Like This tells the story of Annie Beyers — a woman who has practically everything until she wakes from a devastating car collision. After she’s awoke in the hospital, she finds out the past few years of her life surprisingly never happened. The memories of her previous life begin to mesh with the present, and Annie must discern the truth about what’s happened.

See the mesmerizing cover and read an exclusive excerpt!

As the day is coming to a close and I’m falling asleep, sometimes I’ll hear the sound of gravel beneath my feet. It comes to me like a lullaby, repetitive with each footstep, remarkable in its clarity as I long for the place I once called home. They are my footsteps that I hear, the sound of my gait and the moderate, even tempo of my feminine walk as the small stones crunch beneath rubber soles. Immersing myself further into the sound, allowing it to expand, I begin to hear the breeze flowing through the meadow grass that borders the driveway and see the red hues of the setting sun above the woods beyond. I inhale the scent of sweet green.

I pass a small section of four-board fence, one of eight that I once proudly painted, gleaming white on a hot summer day. I’d purchased the paint on a bargain rack, along with two plastic trays and a wide brush, without paying much attention to the proper way to paint a wooden fence. White paint was white paint, I’d thought. Within a year or two of harsh Upstate New York weather, the white had faded and flaked, and now, years later, was chipped and covered in patches of mottled gray that somehow made it seem more authentically rural, and yet sadly unkempt at the same time. It spoke of inexperience. Of city dwellers with soft hands and clean nails. But still, it was my fence. Countless birds had sat there. Red-winged blackbirds. Ravens in sets of ominous threes. The occasional hawk with searching eyes. A small family of chickens. My daughter had climbed those fences. I’d planted wildflowers beneath them. The weeds had flourished. The wildflowers had not. For a few Decembers, I’d hung evergreen wreaths on the sections that fronted the road, the large red bows contrasting with the white snow, offering Season’s Greetings to passersby. The fences sat plainly now, decorated only by a For Sale sign that haunts me daily.

Let’s give it five years, we’d said, on the day we purchased the Yellow House with nervous smiles and the excitement that comes with a new adventure and risky life change. By the end, we’d added more to that number than planned, but not nearly as many as we’d hoped. So after six harsh Catskill winters, seven golden summers, one marriage, one beautiful daughter, six chickens, one horse, two failed vegetable gardens, one lost dream, and countless fireflies and rainbows, I’m walking up the gravel driveway to the home on my hayfield island, one last time. Hannah runs in front of me, skipping and bouncing up the driveway, scanning the gravel for the sparkly ones that she treasured.

Our mailbox sits at the bottom of the driveway, near the road, and I’d walked the length of it every day to retrieve the mail over the years. I’ve just done this for the last time, knowing that the post office would start forwarding our mail the next day. I drop it onto the steps where I’d left the pruning shears.

“Mommy, can I run back to the swing?”

“Okay, but just for a few minutes. It’s almost snack time—hungry for anything special to munch on?” I ask.

Her little face curls into thought. “Hmm—carrots annnnnd apples and peanut butter!” She walks down the sidewalk, running a hand along the bushes. She leans over to smell a bloom. “Will there be lilacs in the new apartment?” she asks.

I turn my head so she can’t see my face and try to steady my voice against the lump that has instantly formed there. “Maybe not lilacs, sweetie. But I’ll bet there’s a park nearby with flowers.”

She shrugs. “Okay.”

“Try to keep your shoes on!” I call, just as she disappears around the corner toward the back of the house. But really, I hope she doesn’t. I wasn’t sure how many more times she’d be able to run barefoot in meadow grass. She had been sick earlier in the week, and I hoped it wouldn’t go to her ears. I wanted her to be able to enjoy these last few hours in our home. She was at an age when childhood memories were efficiently purged by a growing brain, and I knew she would likely not remember anything but a mere hazy feeling of this magical home she’d once lived in. The rest, forgotten.

Leave A Comment