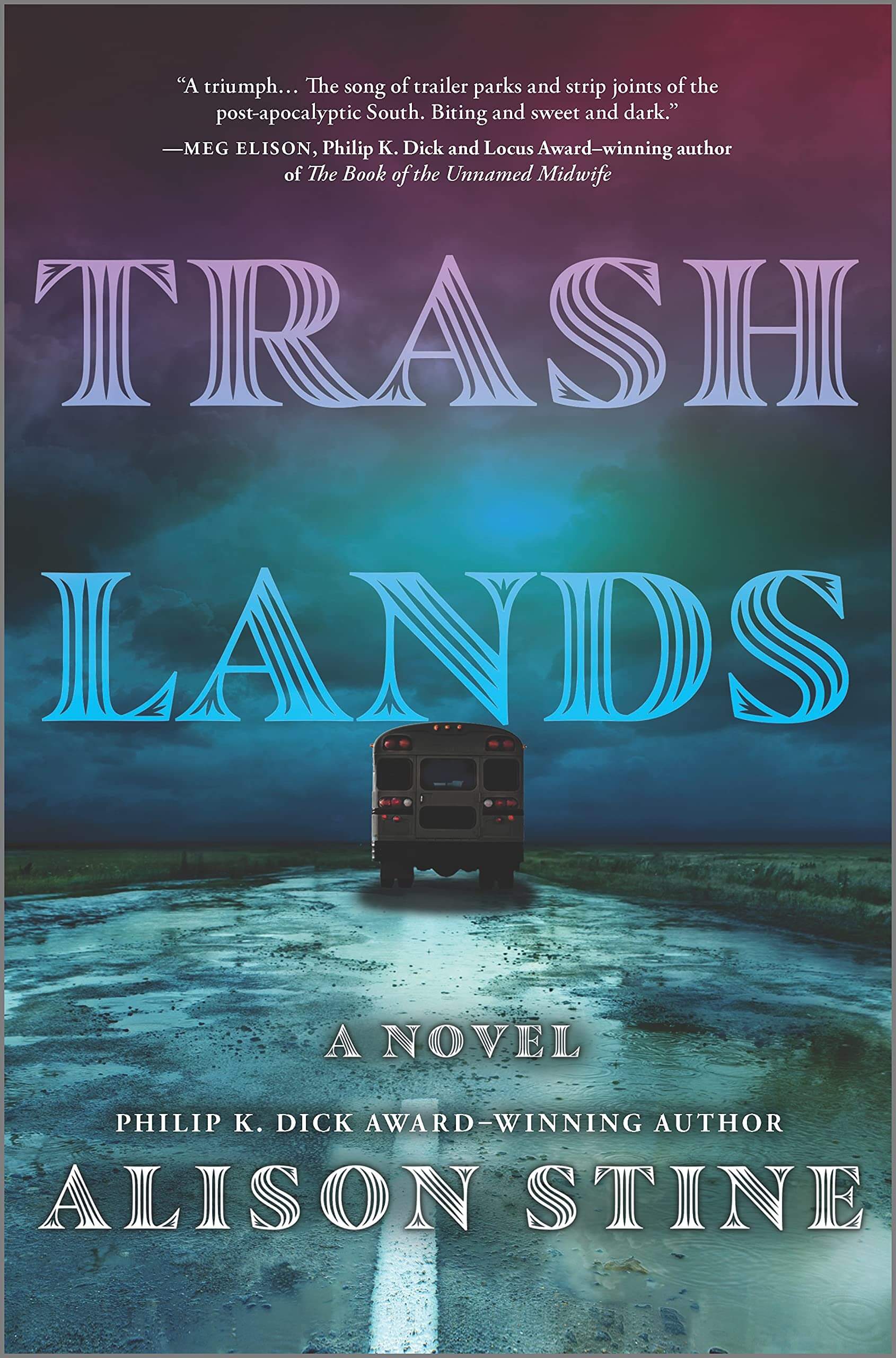

Apocalypse noir and cli-fi may be all the rage right now, but Alison Stine’s Trashlands takes it to a whole new level: a fresh yet gritty angle, logically desperate but hopefully resilient, a mixture about the power of art and the sacrifices everyone makes, regardless of the time and place. Oh—and did we mention it’s about time someone touched on the poverty side of post apocalyptic dark and bittersweet old-meets-future world landscape: the people struggling on the edges of the world where water will rise, sex workers, families in trailer parks, strip joints, individuals finding a home, the painful process of survival—particularly as a parent’s journey in a changed world.

A few generations into the future, plastic is outlawed and has become valuable currency. The coastlines of the continent have been redrawn by floods and tides, and in the region-wide junkyard that Appalachia has become, we discover the Trashlands, a dump named for the strip club at its edge. Then we meet Coral, a “plucker,” pulling plastic from the rivers and woods. In Trashlands, local women dance for an endless loop of strangers and the club’s violent owner rules as unofficial mayor. With her child recruited early on to work in the recycling factories where he’s forced to work, Coral works ferociously in the polluted landscape to save up enough to rescue him, but when she has the time, she makes something amazing: art. When a reporter looking for refuge arrives in Trashlands, Coral is presented with an opportunity to change her life. But is it possible to choose a future for herself?

We talked with Alison Stine about the inspiration behind the novel, the escape of writing poetry, and how she didn’t really change the post-apocalyptic narrative as critics say.

When and what first inspired the idea for Trashlands?

I’ve been a single mom pretty much since my son was born. Those few weeks out of the year when he’s not with me, I try to go somewhere remote and just write. Somewhere with no distractions. I had gone to an old school bus that had been fixed up into a camper. And I couldn’t sleep. My first night, I dreamed about a woman named Coral who lived in an school bus with her partner, a tattoo artist named Trillium. I knew Coral was an artist too, and that she was a mother, a young mother, but that her son was missing. I woke up from the dream and went right into writing Trashlands. It wasn’t the project I had gone to the bus to do, but once I dreamed Coral, she demanded to be heard.

What was your hardest, and easiest task about changing up the typical post-apocalyptic narrative?

I never set out to write a specific genre or type of book, I just want to tell a good story. And this story demanded to be told this way. You have to be true to your book. Aspects that seem natural to me, like having women in charge, women at the center of the story, taking a complex view of motherhood, it took me aback that people have called this radical or new, or not in the typical post-apocalyptic book that we hear about. I feel like women will be the survivors, would lead a new world, especially rural women like the kind I grew up with. But not everyone feels this way. I’m happy to surprise them and I hope I change their mind.

Whether it was during research or the path your characters took, what surprised you while writing the book?

I surprised myself by writing a novel with multiple perspectives. Different characters tell the story with their own chapter or two that goes into their life and past. I had intended Trashlands to just be Coral’s story, in Coral’s voice, as my first novel Road Out of Winter had been in one woman’s voice. But I realized this wasn’t just one woman’s story. It’s the story of multiple people. It’s the story of a community in a junkyard, and how they band together to survive the un-survivable. I think because I had to summon the voices of many characters, I got to know them deeply, and I miss them terribly. I’ve never grieved the ending of a book like I have Trashlands. I want to be back there in the junkyard by the river in the shadow of a club. I fell in love with these characters, and I miss them like friends.

You’ve also published multiple poetry collections. What does writing a novel satisfy that poetry can’t as a writer? And vice versa?

I love the escape that novels offer, both as a reader and especially as a writer. Sometimes you need to disappear. It’s how I take care of myself, by building worlds and exploring them alone, and it’s the only thing I know that captures that delight you felt as a kid, just going into the woods or your backyard and dreaming. I do appreciate how quickly you can wrap up poems. You can finish a poem in a night, or even an hour, and sometimes find a home for it quickly. Novels are such a commitment. You really have to go all in—and go deep—on a story for a long time, for years. With a novel, you have to mean it.

What are you currently reading?

I’m reading the novel Fan Club by Erin Mayer. I love thrillers, mysteries, and truly any kind of slightly scary book that will keep me up late, turning pages.

What are you working on next?

I’m writing a new novel. It starts as more realistic than Trashlands—but it’s going to get creepy and magic real quick.

Leave A Comment