The minute after I received an email invitation to moderate the Viva Latino: Own Voices Writers in Conversation panel, featuring authors I have not only admired but whose work has been so fundamental to my personal evolution, I screamed.

I literally screamed.

I was out on a run and, feeling overwhelmed by the workout I was asking my body to do, I did what I normally do: check my email on my phone. Unhealthy, I know—but in this moment, seeing this email, I was shot through with such a fierce force of motivation that it literally made me howl out with excitement.

Fast-forward to right now, as I am sitting down to digest and process the event, I truly still cannot believe I had the opportunity to host it at the request of my home library system state. The same library system that contributed to raising me as a reader, and if you pair that with having my high school Spanish literature teacher present, asking when I’ll sit down to write my own book, well it turned out to be one of the most magical moments of my life.

I also found myself understanding something I don’t think I truly have before: there is power in conversations, especially conversations among authors and readers that represent a large spectrum of lived experiences across generations.

Absorbing all this in, I knew I wanted to capture the top four things that stayed with me during this significant conversation with Julia Alvarez, Angie Cruz, Reyna Grande and Juan Felipe Herrera.

Oral Tradition in the Latinx communities kept our stories thriving long before we wrote them down in physical books we could touch.

I was reminded of this fact after asking the panelists to share the first book/age when they read a book they felt “seen” in. Julia Alvarez shared that she wasn’t a reader growing up. She was a girl in the 50s growing up in the Dominican Republic under a dictatorship who wasn’t encouraged to get an education. Books—and reading in general—typecaste women in that time as troublemakers. It was through the radio that she fell in love with the art of storytelling.

Juan Felipe Herrera shared that storytelling first became a reality for him through his Mother, who would recite poems, corridos (Mexican ballads) and rhymes she remembered from El Paso, which she picked up during the Mexican Revolution. Hearing this gave me a flashback to all the car rides with my Tio, who would tell us scary stories, or stories about what it was like growing up in Mexico with my Mother. It’s the first time I remember having insight into my Mother’s teenage years. Though, I myself have placed so much value on physical books and stories existing in them, somewhere along the line I forget the impact of oral histories we all carry within us.

Simply existing, we inspire each other.

I believe in the interconnectedness of all in this shared universe. So, this one might be a little biased: Angie Cruz detailing the moment she walked into a Barnes and Noble in the early 90s, after spotting a book in the window with the words “Alvarez” and “Garcia” on the cover. That same book in the window she purchased that day happened to be a book written by one of the other panelists: Julia Alvarez. Angie Cruz later shared how, up until that moment, she had only ever read books by dead white men.

This coincidental moment resulted in Cruz being able to read a fellow Dominican woman’s work, who was a pioneer for her own work. Witnessing such a full circle moment—I still get chills thinking about it. By Julia Alvarez simply writing, her work was able to inspire and be a visible reality for others that look like her to pursue the same path.

Books are a luxury.

I grew up always having access to books. However, trips to the bookstore with my parents to buy new books, like the ones I take my son on now, weren’t something we did. We didn’t have a home library, or even physically own books. The access I had to books was through the used books my mother brought home from houses she’d cleaned and the library. Still, I’ve managed to forget how much of a luxury books are.

When Reyna Granda went to do a reading in Mexico for the first book she ever published in 2012, The Distance Between Us, she noticed that her book cost the equivalent of 200 pesos. The most impoverished people in Mexico make about 100 pesos a day. A copy of her book would cost about two days worth of work wages. This made her realize her family’s reality in Mexico. They couldn’t be readers, because they simply did not have the financial stability to purchase books.

Libraries, Librarians and Teachers.

I connect my love of reading to my Mama quite a bit, so I was curious if a parent also nourished the reader in the panelists. I was wrong in that assumption. Each panelist shared that their parents weren’t readers, and therefore didn’t encourage reading. Julia Alvarez recalls her sixth grade teacher, who could tell she loved stories and was able to convince her (a non-reader at the time) that there were multitudes of stories in books that would interest her and that didn’t contain propaganda from the dictatorship. And after discovering libraries, Alvarez was able to connect with librarians that took an interest in what she was reading and encouraged her by connecting her with similar books. Angie Cruz remembers a teacher taking the extra time to physically walk her over to the library, showing her that this space existed for her. Reyna Grande talked about how her access to books in general only became a reality through the library system after she immigrated to Los Angeles, California. Grande credits becoming a writer to having access to books through the library, because for her “you have to be a reader to be a writer.”

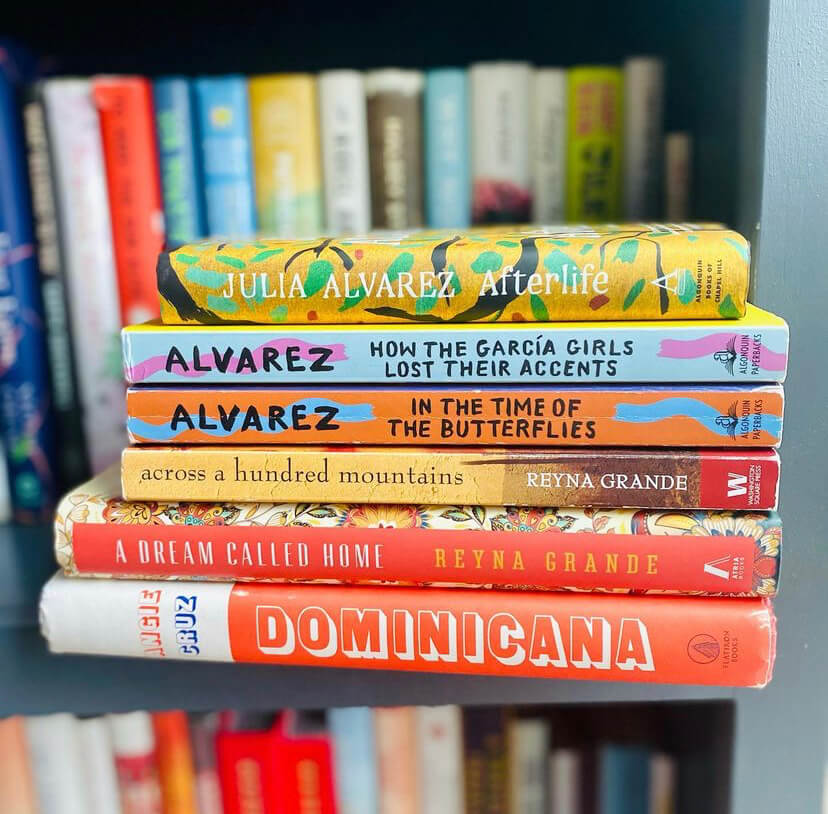

Books to read by the Panelists:

In The Time Of The Butterflies by Julia Alvarez

It is November 25, 1960, and the bodies of three beautiful, convent-educated sisters have been found near their wrecked Jeep at the bottom of a 150-foot cliff on the north coast of the Dominican Republic. El Caribe, the official newspaper, reports their deaths as an accident. It does not mention that a fourth sister lives. Nor does it explain that the sisters were among the leading opponents of Gen. Raphael Leonidas Trujillo’s dictatorship. It doesn’t have to. Everyone knows of Las Mariposas – “The Butterflies.” Now, three decades later, Julia Alvarez, also a daughter of the Dominican Republic and long haunted by these sisters, immerses us in a tangled and dangerous moment in Hispanic Caribbean history to tell their story in the only way it can truly be understood – through fiction.

How The Garcia Girls Lost Their Accents by Julia Alvarez

Uprooted from their family home in the Dominican Republic, the four Garcia sisters – Carla, Sandra, Yolanda, and Sofia – arrive in New York City in 1960 to find a life far different from the genteel existence of maids, manicures, and extended family they left behind. What they have lost – and what they find – is revealed in the fifteen interconnected stories that make up this exquisite novel from one of the premier novelists of our time.

Yo! by Julia Alvarez

Yolanda García–Yo, for short–is the literary one in the family. Her first published novel, in which uses as characters practically everyone she knows, was a big success. Now she’s basking in the spotlight while those “characters” find their very recognizable selves dangling in that same blinding light. But turnabout is fair play, and so here, Yolanda García’s family and friends tell the truth about Yo.

Afterlife by Julia Alvarez

Antonia Vega, the immigrant writer at the center of Afterlife, has had the rug pulled out from under her. She has just retired from the college where she taught English when her beloved husband, Sam, suddenly dies. And then more jolts: her bighearted but unstable sister disappears, and Antonia returns home one evening to find a pregnant, undocumented teenager on her doorstep. Antonia has always sought direction in the literature she loves–lines from her favorite authors play in her head like a soundtrack–but now she finds that the world demands more of her than words.

Soledad by Angie Cruz

At eighteen, Soledad couldn’t get away fast enough from her contentious family with their endless tragedies and petty fights. Two years later, she’s an art student at Cooper Union with a gallery job and a hip East Village walk-up. But when Tía Gorda calls with the news that Soledad’s mother has lapsed into an emotional coma, she insists that Soledad’s return is the only cure. Fighting the memories of open hydrants, leering men, and slick-skinned teen girls with raunchy mouths and snapping gum, Soledad moves home to West 164th Street. As she tries to tame her cousin Flaca’s raucous behavior and to resist falling for Richie — a soulful, intense man from the neighborhood — she also faces the greatest challenge of her life: confronting the ghosts from her mother’s past and salvaging their damaged relationship.

Let It Rain Coffee by Angie Cruz

Esperanza risked her life fleeing the Dominican Republic for the glittering dream she saw on television, but years later she is still stuck in a cramped tenement with her husband, Santo, and their two children, Bobby and Dallas. She works as a home aide and, at night, hides unopened bills from the credit card company where Santo won’t find them when he returns from driving his livery cab. When Santo’s mother dies and his father, Don Chan, comes to Nueva York to live out his twilight years with the Colóns, nothing will ever be the same. Don Chan remembers fighting together with Santo in the revolution against Trujillo’s cruel regime, the promise of who his son might have been, had he not fallen under Esperanza’s spell.

Dominicana by Angie Cruz

Fifteen-year-old Ana Cancion never dreamed of moving to America, the way the girls she grew up with in the Dominican countryside did. But when Juan Ruiz proposes and promises to take her to New York City, she has to say yes. So on New Year’s Day, 1965, Ana leaves behind everything she knows and becomes Ana Ruiz, a wife confined to a cold six-floor walk-up in Washington Heights. Lonely and miserable, Ana hatches a reckless plan to escape. But at the bus terminal, she is stopped by Cesar, Juan’s free-spirited younger brother, who convinces her to stay. As the Dominican Republic slides into political turmoil, Juan returns to protect his family’s assets, leaving Cesar to take care of Ana. Suddenly, Ana is free to take English lessons at a local church, lie on the beach at Coney Island, see a movie at Radio City Music Hall, go dancing with Cesar, and imagine the possibility of a different kind of life in America. When Juan returns, Ana must decide once again between her heart and her duty to her family.

The Distance Between Us by Reyna Grande

Award-winning author Reyna Grande shares her personal experience of crossing borders and cultures in this middle grade adaptation of her memoir, The Distance Between Us–“an important account of the many ways immigration impacts children” (Booklist, starred review).

Dancing With Butterflies by Reyna Grande

In Dancing with Butterflies, Reyna Grande renders the Mexican immigrant experience in “lyrical and sensual” (Publishers Weekly, starred review) prose through the poignant stories of four women brought together through folklorico dance.

Across A Hundred Mountains by Reyna Grande

Winner of the American Book Award, Across a Hundred Mountains is a “timely and riveting” (People) novel about a young girl who leaves her small town in Mexico to find her father, who left his family to work in America–a story of migration, loss, and discovery.

A Dream Called Home by Reyna Grande

From bestselling author of the remarkable memoir The Distance Between Uscomes an inspiring account of one woman’s quest to find her place in America as a first-generation Latina university student and aspiring writer determined to build a new life for her family one fearless word at a time.

Every Day We Get More Illegal by Juan Felipe Herrera

In this collection of poems, written during and immediately after two years on the road as United States Poet Laureate, Juan Felipe Herrera reports back on his travels through contemporary America. Poems written in the heat of witness, and later, in quiet moments of reflection, coalesce into an urgent, trenchant, and yet hope-filled portrait. The struggle and pain of those pushed to the edges, the shootings and assaults and injustices of our streets, the lethal border game that separates and divides, and then: a shift of register, a leap for peace and a view onto the possibility of unity. Every Day We Get More Illegal is a jolt to the conscience–filled with the multiple powers of the many voices and many textures of every day in America.

Jabberwalking by Juan Felipe Herrera

Juan Felipe Herrera, the first Mexican-American Poet Laureate in the USA, is sharing secrets: how to turn your wonder at the world around you into weird, wild, incandescent poetry.

There are so many more things to share about that panel/evening, and I encourage you to watch it. If you are looking for Latinx writers to explore, I also highly suggest you start with these four amazing panlist. I have made a list of their books below. Lastly, I wanted to thank the Prince George’s County Memorial Library System, Frederick County Public Libraries, and Charles Country Public Library as part of the Maryland Libraries Together for the opportunity to moderate this discussion.

Thanks for the reflections Lupita, with gratitude from the Maryland Libraries community! – Nick B./PGCMLS