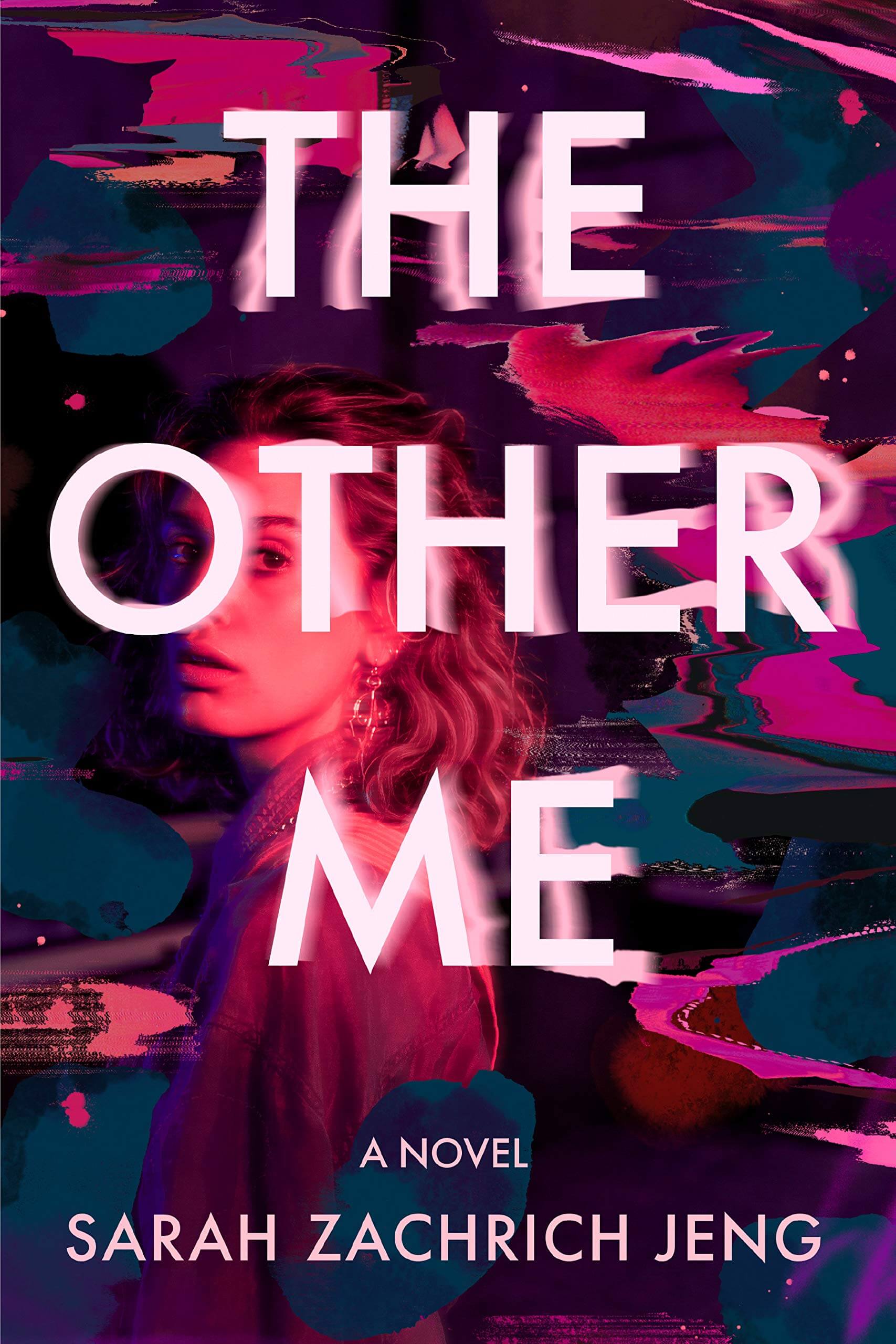

August guest editor Sarah Zachrich Jeng always had a flair for the morbid and mysterious; and her debut novel The Other Me is perfect for this month’s Get Lit With a New Cross-Genre theme. This inventive read is a surprising combination of two of our favorite genres: suspenseful psychological thriller meets a reinvention of the time travel narrative. It’s Is somehow Black Mirror-esque yet relatable, exploring shifting realities and coming into one’s identity.

After all—who hasn’t wondered what alternate versions of their life might look like?

The Other Me circles around the two lives of one person: The one Kelly wanted—and the one that wanted her. Kelly’s birthday should be like any other night. One minute Kelly’s a free-spirited artist in Chicago going to her best friend’s art show. The next, she opens a door and mysteriously emerges in her Michigan hometown. Suddenly her life is unrecognizable: She’s got twelve years of the wrong memories in her head and she’s married to Eric, a man she barely knew in high school.

Racing to get back to her old life, Kelly’s search leads only to more questions. In this life, she loves Eric and wants to trust him, but everything she discovers about him—including a connection to a mysterious tech startup—tells her she shouldn’t. And strange things keep happening. The tattoos she had when she was an artist briefly reappear on her skin, she remembers fights with Eric that he says never happened, and her relationships with loved ones both new and familiar seem to change without warning. But the closer Kelly gets to putting the pieces together, the more her reality seems to shift. And if she can’t figure out what happened on her birthday, the next change could cost her everything…

We talked with Sarah Zachrich Jeng about her favorite cross-genre thrillers, toxic masculinity, and turning the familiar wish fulfillment trope on its head.

How did you come up with the alternate reality concept of The Other Me?

I’ve always loved SFF and cross-genre fiction, especially stories that combine the supernatural or speculative with contemporary realism, so it wasn’t much of a stretch for me to embed an alternate-life narrative into a domestic suspense novel. I tend to ruminate about the past, and I can trace the effects of certain choices or events on the course of my life, so that road-not-taken theme was something I wanted to explore.

At the time I came up with the idea, I was also dealing with being in my thirties and a parent with a very sedate life, when previously I’d played in rock bands and been fairly wild. Quite honestly it would have been self-destructive to continue with the lifestyle I had in my twenties, but there were still adjustments to my self-concept that went along with that shift into being more “conventional.” Writing The Other Me, with a main character who starts out being an artist and then suddenly isn’t, was one way I worked through some of those issues.

Readers are hungry more than ever for cross-genre books. Did you start with the idea of a psychological/domestic thriller first, or the alternate reality narrative?

Not to give too much away, but right from the start I approached the book as a way to turn a familiar wish fulfillment trope on its head, and it was interesting to me to figure out the mechanics of how that would work and why the switch in Kelly’s life is so sudden from her perspective.

When I started writing, I had no idea that The Other Me would be a thriller. It was originally going to be upmarket/literary with a speculative element, and as such, it moved more slowly and had a very different ending. During revisions, I tightened up the pacing in order to keep the focus on Kelly’s attempts to find out what had happened to her life. Between that and the vaguely sinister suburban setting, it made the most sense for my publisher to position it as suspense/thriller.

What do you want readers to take away from the themes of discovering and keeping one’s identity, free will, and toxic masculinity?

We may like to think that we’re individuals not subject to the influence of others, but our identities are shaped by our circumstances and the company we keep. We’re also defined, to a large extent, by the way others see us. When Kelly gets plucked out of her life in Chicago, she’s no longer an artist—not just because she’s now in a reality where she didn’t go to art school, but because no one in her new life thinks of her as an artist.

I made a conscious choice not to have her be successful at the opening of the book to make it clear that even though her life is not ideal, it’s the one she’s chosen for herself, and then she has that taken away. I wanted to introduce some ambiguity as well, to make her unsure about whether she might want to stay in her new life, and that would have been harder to do if she had already found success as an artist. She flirts with the idea of letting her new identity become who she is, because I wanted to show how easy it can be for outward appearances to work their way inward to the core of a person. A lot of her inner conflict comes from the fact that her outside doesn’t match her inside.

The theme of free will is bound up in the question of who gets to be the protagonist, both in fiction and real life. Normally in a story like this, the main character would be the person who takes the action that leads to the inciting incident, but in this case, Kelly is the one acted upon. She’s collateral damage. She is at the center, but her centered-ness is based more on an idealization of her than her as an actual person with agency and goals for her own life. This happens all the time to women in a much more mundane way. There’s still a cultural expectation that a woman in a heterosexual partnership will allow her professional or creative ambitions to take second place to family life, whether it’s motherhood or supporting her partner’s career. People look askance at a woman who is definite about not wanting to have children, or who “neglects” her family in order to pursue an artistic endeavor, in a way they don’t at a man. Kelly has made a choice to focus on her art, but then her choices are erased in a manner that suggests to her, alarmingly, that maybe she was never meant to be an artist.

Regarding toxic masculinity, I read Kate Manne’s Down Girl a while back and it really opened my mind about what misogyny is. It’s not hatred of women so much as a mechanism to control them and keep them in a prescribed range of roles in society. Toxic masculinity is similar: it limits men to certain emotions and certain ways of interacting with the world, including women. It furthers the cultural narrative that men have to be dominant. Like misogyny, it can have a relatively benign appearance. But if a man sees a woman as a prize to be won, it doesn’t matter how nice he is to her.

What are some of your favorite cross-genre thriller books or authors?

The Shining Girls by Lauren Beukes, about a time-traveling serial killer from Depression-era Chicago, is one of my top ten. I’ve devoured everything I’ve picked up by Simone St. James. And finally, I recently read The Other Black Girl by Zakiya Dalila Harris, which blew me away with how deftly it ratchets up the tension while weaving together office satire, social commentary, and a generous dash of sci-fi.

If you could imagine an alternate reality of your life, what’s the first thing that comes to mind?

Not a life I would want to be living right now! I made some bad choices when I was younger, but some good ones, too.

Leave A Comment