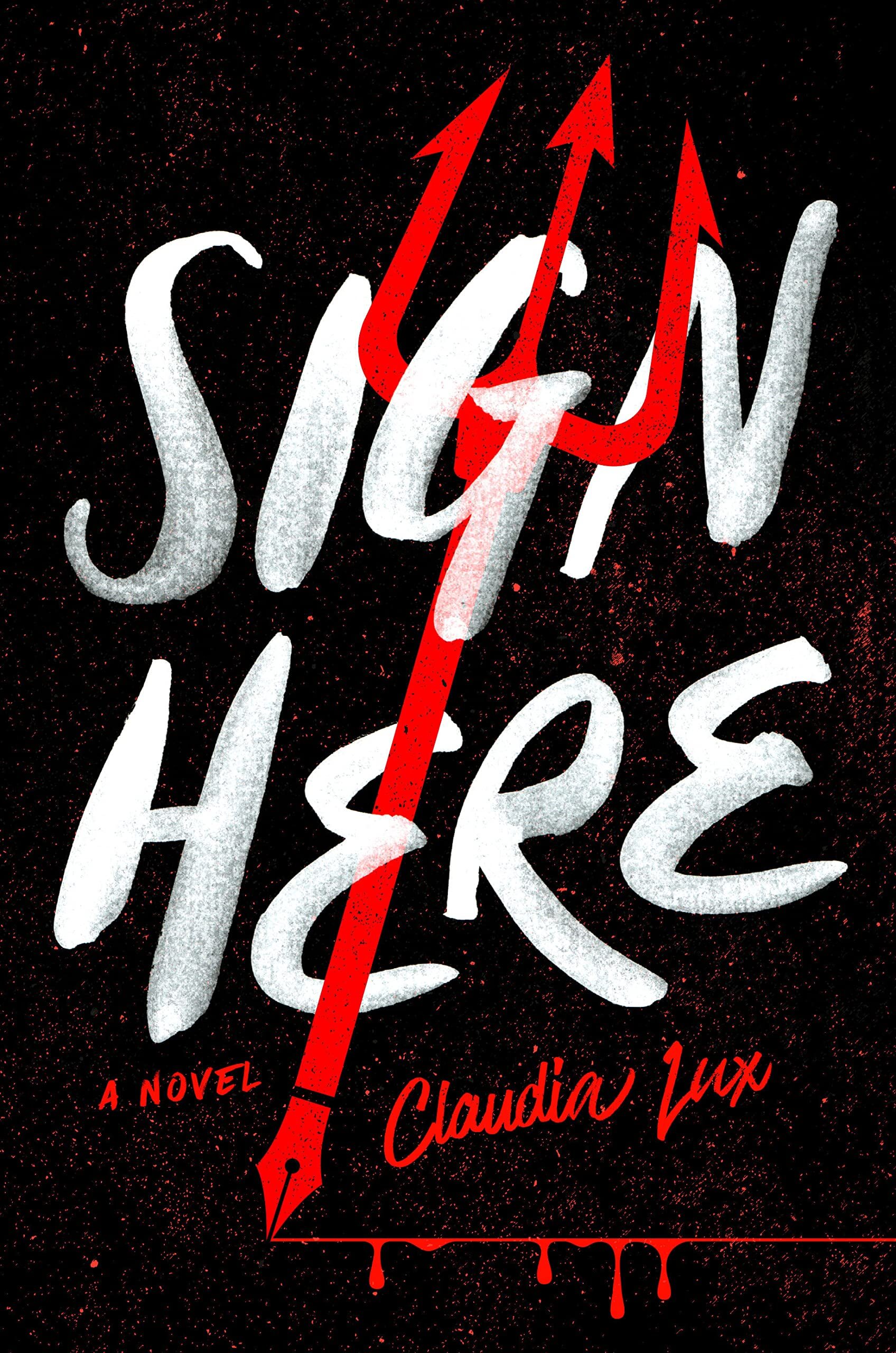

Meet Claudia Lux, the debut author of the wildly dark book pick that we’re all reaching for during October. Sign Here is the perfect combination of dark humor, paranormal horror and satire, rooted in the unique premise (and incredible world-building) of being an employee in the depths of Hell. Think the sticky web of wealthy family secrets in Revenge meets the The Good Place’s absurdist take on a workplace afterlife.

In Sign Here, Peyote Trip is one of the countless “employees” living out his afterlife sentence in Hell. And while the Hitlers and the sex traffickers of the world may reside in the worst rungs, there are several places dedicated to the liars, the petty thieves, the low-grade jerks. In Hell, time (often measured in millennium) and hunger (main cravings: salt and fresh air) have no defining boundaries, none of the pens work, and the bars only serve Jägermeister. In order to get promoted, Peyote is dedicated to collecting as many souls as possible, including a member of the bougie Harrisons—a wealthy, secretive New England family back on Earth—to sign their soul away to him, and he grows obsessed with the family as they embark on their New Hampshire summer vacation. His desperation and ambition to meet his quota intersects with the Harrison’s intergenerational secrets and scandal, plummeting them all into the family’s dark past in a way no one sees coming.

This is an electrifying unexpected story about what life looks like after we stop living, and more so, what it looks like when we decide to live on anyway.

Read on for our exclusive interview with Claudia Lux on how she used peoples’ interpretations of Hell as an influence, her favorite parts of creating Sign Here‘s world-building, and contemporary poetry.

You came up with this concept while riding the L train in New York one day. What really inspired it while you were sitting there?

The book begins on the L train because I lived in Brooklyn right after college and that opening scenario was a regular occurrence during my commute to work. But I actually came up with the idea for the novel in a hotel room in Texas almost a decade later. I was streaming some show online and the same insurance ad began for the billionth time, and I was so frustrated that they wouldn’t even bother to mix the ads up, to give their captive audience a little variation at least, that I yelled out loud, “this is hell!” Then I looked around at my surroundings: the bright, clean hotel room, the stocked mini-fridge, the feather-filled pillows, and realized that in that moment, my definition of hell was pretty damn fluffy. After that I started noticing it more: how quick we are to compare our momentary discomfort to eternal damnation; how low the colloquial bar has gone for suffering.

The worldbuilding is great – there are things from a writer’s personal hell, like none of the pens work. Did you poll people to see what their own personal hell would be like to make all those dozens of extra elements in “hell” come to life?

Yes, that’s exactly what I did! Once I had that thought in that hotel room, I started getting curious about the annoyances that pushed other people to exclaim some variation on that theme. And if you say you haven’t, I don’t believe you! We all have those things that drive us completely up a wall, without any fire or brimstone. But those things are also sources of connection and humor. People would get so excited when I would bring the topic up, everyone having their own “hellish” moment to add, that it united everyone: to share in one and other’s annoyances like that, to commiserate. Unsurprisingly, a lot of those moments I heard about occurred at work, and the book evolved from there.

How did you decide to intertwine the grittiness of working in Hell with a bougie powerful family on earth as the target?

That fell in line with the “fluffy hell” realization: the role that privilege plays in the definition of struggle. I started thinking about how a Deals Department employee might be drawn to the combination of low tolerance and high expectations that stems from privilege, especially the long-cemented kind of generational privilege that tends to come with New England summer homes. I imagined it would be very appealing, easy work. But the thing about struggle is that we are all operating on our own scales, balanced by our own understanding of weight. The worst thing that has ever happened still feels like the worst thing that ever happened, regardless. So even with the privilege of intergenerational financial stability, families like the Harrisons have their own struggles, their own skeletons in the closet. I wanted to see what happened when those two concepts came together: the totally valid belief that a family with so much privilege would be an easy and possibly deserving target for a deal (and, with it, a one-way-ticket to hell) and the reality of their inner lives. Not only for the characters, but for the reader. How, in the end, would the reader want it to play out for the Harrisons? Would it be different from what they might’ve wanted for them in the beginning?

Was it a surprise how the story unraveled for you?

With anything I’ve written, I always start at the very first page with a character or maybe two in mind, and then keep writing straight through until the end. Historically, I have never storyboarded or planned ahead, outside of the broadest strokes. I am along for the ride as much as the reader, which I think can add to the sense of suspense. I am in suspense too!

What is something you’d like readers to take away from this novel?

Through my career as a social worker, I found that people like to make big, sweeping generalizations in the theoretical, but when it comes down to individual humanity, things get more complicated. I think the best thing we can do as a society is remember the humanity in all of us, first and foremost.

What was your favorite aspect of Hell to write about?

I’m not going to lie, I cracked myself up a lot as I was writing this book. I loved writing Jack’s bar and imagining what would go into an underground (no pun intended) beer operation in hell. I also loved writing Trey: really letting my inner jackass out. But honestly my favorite part about Hell was the Hell Orientation I wrote to go alongside the novel. It didn’t fit in the book, but you can find it on my website claudialux.com and it goes into detail about the layout of hell and the ideology behind getting the best deals.

What do you read to get inspired?

My dad, poet Thomas Lux, always said writing is reading, and I couldn’t agree more. I read constantly. I prefer hard copy books, reading on a screen doesn’t quite feel real to me (although I love thrillers on audiobook!) and whenever I finish a book, I have a practice of transcribing the lines I’ve underlined into my journals, along the tops of all the pages. I’ve developed a code for underlining with symbols that range from “hot damn, this is brilliant” (those are the ones that go into my journal) to “this is/was exactly me as a human” to “try this style” because reading is the best way to get better as a writer! But if we’re talking about a genre, whenever I feel uninspired, I read contemporary poetry. While plot and story are, obviously, extremely important to writing fiction, for me, the joy comes from my love of words: their meanings, their sounds, the way they feel in my mouth. Poetry carries the highest, unfiltered hit. The poets I return to whenever I get stuck are Jeffrey McDaniel, Bill Knott and Ross Gay, among others. And Thomas Lux! Not just because I’m his daughter. He was a giant.

Leave A Comment