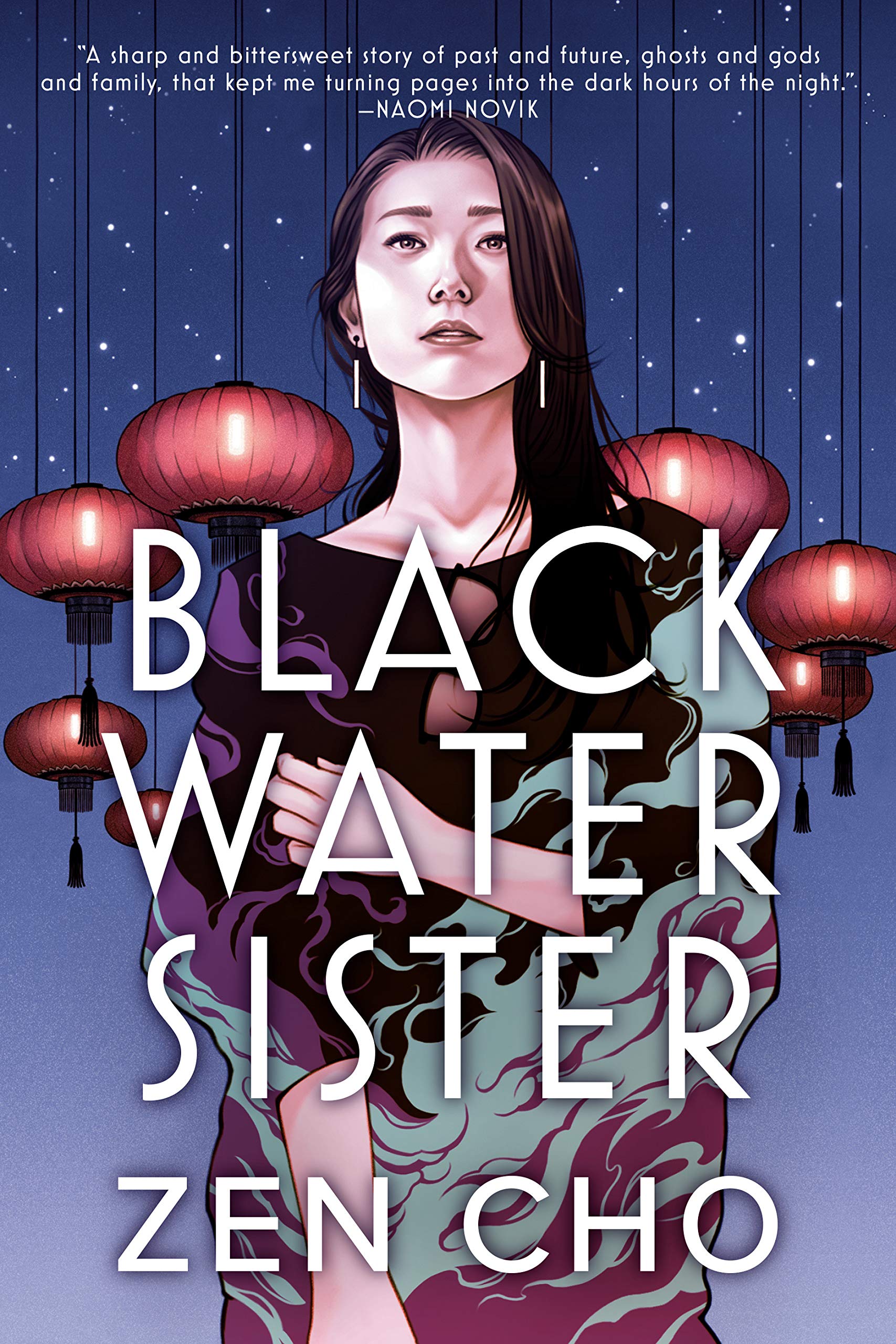

This May, fantasy fans have a great new TBR pick with the release of Zen Cho’s Black Water Sister. Typically known for her Regency-inspired fantasy novels, Sorcerer to the Crown and The True Queen—praised by NPR and Washington Post—Black Water Sister pivots to contemporary fantasy, with a compelling story inspired by Asian folklore that Publishers Weekly calls “a must-read fantasy.”

Black Water Sister follows Jessamyn Teoh, closeted, broke, and moving back to Malaysia—a country she left when she was very young—to live with her parents. When she arrives, Jessamyn realizes the voice in her head she thought was related to stress, is really her estranged grandmother, Ah Ma, an avatar for a mysterious deity known as the Black Water Sister that’s seeking revenge on a business magnate that offended the god. Drawn into a world of gods, ghosts, and family secrets, Jess finds that making deals with capricious spirits is a dangerous business, but dealing with her grandmother is just as complicated. Especially when Ah Ma tries to spy on her personal life, threatens to spill her secrets to her family and uses her body to commit felonies. As Jess fights for retribution for Ah Ma, she’ll also need to regain control of her body and destiny—or the Black Water Sister may finish her off for good.

Sharp, humorous, bittersweet, full of heart, and a touch of suspense, Black Water Sister presents a blend of culture clashes, gods, family secrets and bonds, the ghosts of past and future, and the constant struggle that is finding one’s personal identity.

We talked with Zen Cho about the cross-cultural experiences that have shaped her writing and life, the intersections of queerness and science fiction, and the book she’d read over and over. Want more Zen Cho? Don’t miss the Ten Book Challenge: Zen Cho’s Book-It List.

As a Malaysian fantasy writer based in the UK, have you found cross-cultural aspects between Malaysian and British culture that have influenced your writing? If so, can you tell us a little bit more about them?

I’d say cross-cultural experiences have shaped my entire life. The state of Malaysia was only formed in 1963, and it’s still influenced by more than a century of British colonialism. Though I’m ethnic Chinese, I grew up in Malaysia speaking English with my family and reading books by authors from the UK and America. The first book I read by myself was a picture book called Santa’s Busy Night, a funny choice for a non-Christian child living in a tropical country who didn’t celebrate Christmas!

So when I came to the UK as a young adult, it was already somewhere I knew, in a way – like a character in a beloved book. Of course, living here is very different from knowing a country through its literature and impact on my own country. I would say the biggest difference was directly encountering racism and white privilege. The Chinese are a substantial minority in Malaysia, with significant economic clout – I might have been told to “go back to China” by the more excitable ethnonationalists in Malaysia, but I’d never had stuff thrown at me in the street for having the wrong skin colour. What was even harder was having white progressive friends deny that what was happening to me in the UK was founded in racism.

All of this inevitably had an impact on my writing. I write often about characters who bridge cultures, like Asian American Jess, or Zacharias Wythe in my first novel Sorcerer to the Crown, who is England’s first Sorcerer Royal of African descent. I tend to explore the stories of people who live on the borders, histories and experiences that diverge from the perceived norm.

In Black Water Sister, we’re introduced to Jessamyn, a Malaysian-American whose life seems to revolve around the intricacies and demands of others most notably through the ghost of her grandmother, Ah Ma. Can you talk about the intersections of queerness and science fiction in this novel?

The ghosts in Black Water Sister, especially Ah Ma, can be read as a literalisation of how history affects our present, a narrative representation of the idea that the past will always come back to haunt you. I think that’s especially true for histories that are suppressed, particularly histories of trauma. I suppose where that intersects with queerness is that Jess’s queerness is also something that is suppressed, not spoken of.

The point the book makes is that that enforced silence damages not only the person forced to be silent, but the people around them, too. That suppression and denial of truth, the shame around it, are all an injury done to the world.

How is Black Water Sister different from your previous books and novel? What made you want to write the novel?

My previous full-length novels, Sorcerer to the Crown and The True Queen, were light-hearted historical fantasies, inspired by Georgette Heyer’s Regency romances and the country house comedies of P. G. Wodehouse.

Black Water Sister is my first novel to be set in Malaysia and in the present day (pre-COVID). It’s also the novel that is most personal to me, drawing inspiration directly from my own life. I’ve known for years that I would want to write something like it some day. I was just waiting for the spark – which came when I read Jean DeBernardi’s The Way That Lives in the Heart, an anthropological study of Chinese popular religion and spirit mediumship as it’s practised in Penang, Malaysia. The idea of a reluctant medium encountering these powerful, mysterious spiritual forces was what brought the book into being.

In your experience writing fantasy, what perceptions of your writing have you found hard to deal with?

There often seems to be a sense that writers from underrepresented backgrounds, even writers of an “unserious” genre like fantasy, must necessarily write worthy po-faced books that convey important messages. I love to laugh and I love a comfort read; most of my favourite books are funny or swoonily romantic or, ideally, both. My stories deal with serious issues, too, but I do sometimes feel that because they’re funny their seriousness can be overlooked, or because they engage with racism and sexism and imperialism, people don’t think they’ll be fun reads.

If you had to read one book over and over again, what would it be and why?

Anne of Green Gables by L. M. Montgomery. It’s a childhood favorite. Escapist, cosy, about finding your community and growing up.

Leave A Comment